Tuesday, March 31, 2009

Monday, March 23, 2009

Of Lionel by J. Lessing Teitler

like you arriving unannounced so late on shabbas

unravel allegories of twinkling wit and trembling fear--

you have to be like a shaman

to see the signs

as it is above

it is below

its true ya know--

where did the missing shofar go?

place the chicken soup just so

4 more inches back to the right

on the shabbas tinfoil

over gas on low

so it won't evaporate tonight

that broth,

those misshapen heavenly matzoh balls

home cooked by the wife of an angel

brought all the way from Brooklyn--

look in the bottom of the fridge

can you believe all the stuff they bring me?

why me?

can you still hear Ziprin's voice?

the mameloschn inflections,

of Abulafia,

of old lower east side

co-mingled with bebop's crescendos,

a devout hipster confection

sacred and profane

is it any wonder Charlie Parker

would come to his table

to chill?

there he is stepping around frozen horses

dodging rats as big as cats

he didn't stay much in school

but he went to school

they let him pass--

when he was very young,

he didn't even know that people weren't Jewish

he rented horse and buggy, moved uptown

he drove it in the cold

to 3rd and 17th

he learned

that America had been good to the Jews

like some Valentino

Lionel, all lush eyebrows and luscious lips,

enchanted the Kansan girl

Marlon Brando stole away with

at the Actors Studio

sitting on the corner

upright on his folding stool

his advance toward shul

undeterred by East Broadway

sweltering in the summer sun

do you see his finger pointing

toward the window on the second floor,

he lived there as a boy

next to the House of the Sages,

or there

behind Bialystoker,

where the Home of the Sages stood

after the schism

enough room now to nap or break bread

where Harry taped the songs of his grandfather's world--

its not called Misirlou! the melody is aaaaaancient!

this spring will bring no seder

the spare one last year

like a comedic last supper--

don't woooorry about it!

you have to pour the wine so every cup overflows

you haaaave to!

a solitary sprig of parsley to share

we climb around each other

careful of Sheba's settee

to empty the collected drops of plagues into the commode--

periodic flushing

oddly not incongruous

with the bare joy of our convenant

the prayers covered

in his knowing sing-song drone

in this late winter of his passing over

he announced

I like turtles very much

and told me

my name meant planter of date trees

and that angels morph more easily than people

they are more elastic, right?

he spoke of

"highly confidential material

to soften our hearts. . . .

of flirting with terminating angels

beckoning to cross the river styx. . . .

thats how it happens, ya know

thats what they're called, ya know. . . .

what do you think, I'll be here forever?"

"this time is different

are you listening?

its not the doctor who cures you

he is the agent of heaven. . .

I have only one heart to lose for my people, thank god!"

j. lessing teitler

march 2009

Saturday, March 21, 2009

A Radio Documentary by John Kalish

Rabbi Abulafia's Boxed Set

Lionel Ziprin passed away last week on New York’s Lower East Side. Rabbi Abulafia’s Boxed Set tells the story of Ziprin's grandfather, a New York City rabbi who recorded 15 LPs of Jewish liturgical music with the eccentric ethnomusicologist Harry Smith in the 1950's. Ziprin’s life mission was to find a record label to distribute these recordings. He was 85 years old when he died. Today in his memory, we are rebroadcasting Jon Kalish’s award-winning documentary.

Lionel Ziprin passed away last week on New York’s Lower East Side. Rabbi Abulafia’s Boxed Set tells the story of Ziprin's grandfather, a New York City rabbi who recorded 15 LPs of Jewish liturgical music with the eccentric ethnomusicologist Harry Smith in the 1950's. Ziprin’s life mission was to find a record label to distribute these recordings. He was 85 years old when he died. Today in his memory, we are rebroadcasting Jon Kalish’s award-winning documentary.*****

For more than two years in the 1950's, avant-garde ethno-musicologist Harry Smith recorded a Lower East Side Rabbi's cantorial music, folk songs and Yiddish story-telling. The Rabbi's eccentric grandson, 81-year old Lionel Ziprin, is hoping to re-release a condensed version of this material. It's a holy mission for him. The program you are about to hear was produced for KCRW by Jon Kalish. It has been honored with this year's Gabriel Award recognizing programs that uplift the spirit, sponsored by the Catholic Academy for Communication Arts Professionals. Originally aired in December, 2005, we broadcast it tonight on the occasion of the Jewish New Year, Rosh Hashanah, which begins this evening.

Santa Monica-based public radio station KCRW commissioned veteran New York City public radio reporter Jon Kalish to produce the documentary. Kalish has covered the Orthodox Jewish world for NPR and other news organizations for 22 years. He was producer-in-residence at KCRW in 2000 and has produced original documentaries on two other New York characters -- Jimmy Breslin and Spalding Gray -- for the station.

"To my ear, Ziprin sounds uncannily like the late Lenny Bruce. But, unlike the comedian, Ziprin hangs out at a Lower East Side yeshiva and his life has been a lot wilder," said Kalish, who shares a Manhattan loft with his painter wife and two Siamese cats. "Of the hundreds of radio stories I have done in the last 30 years, this is hands down my all-time favorite."

Kalish first met Ziprin in 1998 when one of the reporter's elderly Yippie friends introduced him to the man. Kalish did a short radio piece and a newspaper article about Ziprin's rescue of the 15-LP's his grandfather, Rabbi Nuftali Zvi Margolies Abulafia, recorded with the eccentric Harry Smith. Kalish knew the story would make a compelling radio documentary.

NY Times - Lionel Ziprin, Mystic of the Lower East Side, Dies at 84

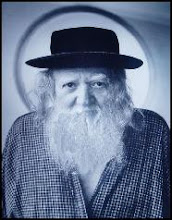

Lionel Ziprin in 2006 in his apartment on the Lower East Side.

By William Grimes

By William Grimes“We are not after all intended to be consumed.”

So begins Lionel Ziprin’s “Sentential Metaphrastic,” a “poem in progress” of more than a thousand pages. “I reduced it to 785 pages,” Mr. Ziprin told The Jewish Quarterly in 2006. “I call it the longest and most boring poem since Milton’s ‘Paradise Lost.’ ”

Many more poems by Mr. Ziprin remain to be discovered, inscribed on spiral-bound notebooks and stuffed into a closet in his apartment on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. And that is nowhere near the half of it. Also in the apartment are the Jewish liturgical chants intoned by Mr. Ziprin’s grandfather, untold hours of sacred music that Mr. Ziprin tried for more than half a century to bring to the wider world.

This legacy now passes to his family — whether to delight or puzzle posterity, no one knows. Mr. Ziprin, a brilliant, baffling, beguiling voice of the Lower East Side and the East Village in all its phases — Jewish, hipster and hippie — died last Sunday in Manhattan. He was 84. The cause was chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, his daughter Zia Ziprin said.

For decades, Mr. Ziprin, a self-created planet, exerted a powerful gravitational attraction for poets, artists, experimental filmmakers, would-be philosophers and spiritual seekers.

He ran his apartment, on Seventh Street in the East Village, as a bohemian salon, attracting a loose collective that included the ethnomusicologist Harry Smith, the photographer Robert Frank and the jazz musician Thelonious Monk, who would drop by for meals between sets at the Five Spot. Bob Dylan paid the occasional visit.

There the art of conversation took a backseat to the art of listening to Mr. Ziprin hold forth for hours at a stretch on magic, interplanetary rhythms, angels, apparitions and Jewish history.

“He was larger than life and so far beyond a certain kind of description that I am bamboozled,” said Ira Cohen, a longtime friend. “He was much larger than a poet, though that’s hard for me to say, as a poet. He was one of the big secret heroes of the time.”

Often categorized as a beatnik, he created an artistic circle that overlapped with the worlds of jazz and beat poetry but remained distinct and apart. A poet prey to visions and hallucinations, a philosopher, a Jewish mystic with a deep understanding of the kabbalah, an enthusiastic consumer of amphetamines (legal at the time) and peyote (also legal) — he was all of these, and something else besides.

“He combined Old World mysticism and New World craziness,” said the poet Janine Vega. “He really was one of the great white magicians of the era.”

Mr. Ziprin was born on the Lower East Side and, after his parents separated when he was a small child, lived with his mother and her parents. The decisive influence on his life was his maternal grandfather, the rabbi Naftali Zvi Margolies Abulafia, an immigrant from Galilee who founded the Home of the Sages of Israel, a yeshiva on the Lower East Side.

The home atmosphere was devout.

“I thought I was living in the Bible,” Mr. Ziprin said in a documentary produced by Jon Kalish for public radio in 2006. “ My grandparents were like biblical people. The only problem I had as a child, I looked outside, and there were automobiles. There’s a big contradiction.”

While undergoing a tonsillectomy, young Lionel — called Leibel or Leibele by his family — was badly overanesthetized. After emerging from a 10-day coma he developed St. Vitus’s Dance and epilepsy. He was seized by fits of uncontrollable laughter and experienced hallucinations. For the rest of his life, he saw visions and conversed with the spirit world.

Physically unfit for military duty, Mr. Ziprin began writing poetry after attending Brooklyn College and worked at an assortment of extremely odd jobs. He helped create a short-lived puppet show called “Kabbalah the Cook” for television. For $10 apiece, he wrote the text for a series of war comic books published by Dell.

In 1950 he married Joanna Eashe, a dancer who made a living as a hand and foot model. In the early 1950s the couple started a totally unsuccessful greeting card company, Ink Weed Arts. She died in 1994.

Mr. Ziprin’s poems, including “Math Glass” and “What This Abacus Was,” appeared here and there in magazines like Zero, but he barely bothered to pursue a career. A poet in the prophetic tradition, he did not so much write as open himself up to otherworldly voices.

“He would read the stuff we published and would have no idea that he’d written it,” said Judy Upjohn, who, with Sandy Rower, published a selection of Mr. Ziprin’s verse in “Almost All Lies Are Pocket Size” (Flockaphobic Press, 1990).

Clayton Patterson, who is writing a history of the Lower East Side, filmed Mr. Ziprin reading his “Book of Logic ” and organized a screening of 10 two-hour installments at Anthology Film Archives in 1989. “The first night there was a full house,” he said. “By the third night there were three people, besides Lionel and myself. That ended the series.”

Mr. Smith, the ethnomusicologist who produced the seminal Anthology of American Folk Music for Folkways Records, heard Mr. Ziprin’s grandfather chanting at a public celebration and became obsessed. Setting up sound equipment in the rabbi’s yeshiva, he spent two years recording hundreds of hours of Hebrew liturgical chants, along with Arabic songs and Yiddish stories, which were distilled into 15 long-playing records.

Shortly before his death in 1955, the rabbi begged his grandson to bring the records to a wider audience, inspiring a half-century quest whose end remains uncertain. Folkways released one album from the set, but for religious reasons, family members objected to further distribution of the material.

In the late 1960s Mr. Ziprin’s wife took the children and moved to Berkeley, Calif., plunging Mr. Ziprin into a spiritual crisis. It was resolved when, acting on instructions from his grandfather in a dream, he returned to the Judaism of his youth and to the Lower East Side, moving into his mother’s apartment on East Broadway to care for her until her death in the late 1980s.

From the mid-1970s until his death, Mr. Ziprin spent his days studying the Torah and other texts at what was once his grandfather’s yeshiva. He held court at his apartment. He scribbled thoughts on postcards and sent them to just about anyone.

He also searched for someone willing to produce his grandfather’s records. As the years went on, and some of the tapes were lost to fire, flood and theft, the mercurial and often cantankerous Mr. Ziprin often seemed to be sabotaging his own cause, eager to disseminate his grandfather’s legacy but reluctant to let it go.

Briefly it looked as if the composer John Zorn had secured the rights to release the records, but Mr. Ziprin could not let go. At his death, the Idelsohn Society for Musical Preservation had made a compilation CD from the material that seemed to please Mr. Ziprin, clearing the way for the production of a full boxed set.

A man of many words, he managed to write his self-portrait in just a few:

I have never been arrested. I

have never been institutionalized.

I have four children. I am in

receipt of social security benefits.

I am not an artist. I am not an

outsider. I am a citizen of the

republic and I have remained

anonymous all the time by choice.Tuesday, March 17, 2009

David Katz meets Lionel Ziprin, mystic, maven and maverick of New York’s Lower East Side

‘Angels are just one more species’‘But subtle is that entry when it comes. It comes like floss. It rides on an ability, making one of two. It makes also a mystery, replacing common light’ - Sentencial Metaphrastic ‘The Jews will have to leave for another planet - Jupiter’ - Lionel Ziprin, Purim 2006 | | ||

| | |

Mon, March 16th 2009 - 20th Adar, 5769 The Jewish Quarterly ![]()

Orthodox Judaism, with its grey-bearded congregants in pure white shirts, tallissim, long black coats and wide-brimmed fedoras, laying tefillin and softly dovening in dimly lit shuls, may seem irreconcilably opposed to the secular libertines of the mid-twentieth-century avant garde, devotees of all that is modern and against the grain, practising their own rituals at art openings, poetry readings, happenings and ‘scenes’, but in the life and times of Lionel Ziprin they merge into a rich and strange tapestry of culture and history.

Poet, artist, Kabbalist, descendent of mystics and, some say, mystic himself, Lionel Ziprin has spent a lifetime in the artistic ferment and social upheavals of the Lower East Side, a fertile incubator of culture, counterculture, religion and politics for more then a hundred years. His life straddles the LES of Henry Roth (Call It Sleep) and Michael Gold (Jews Without Money), as well as the East Village of Thelonious Monk and Allen Ginsberg. Ziprin penned comic books after the war, lectured on the Zohar in the sixties to Bruce Connor and Ira Cohen, composed a thousand-page epic poem entitled Sentencial Metaphrastic, (‘I reduced it to 785 pages. I call it the longest and most boring poem since Milton’s Paradise Lost’). He nurtured the work of his friend Harry Smith, who recorded the liturgical music of Ziprin’s grandfather, the eminent Orthodox rabbi and Kabbala scholar Naftali Zvi Margolies Abulafia, at his yeshiva, the legendary Home of the Sages of Israel, on the Lower East Side, in the early fifties.

‘I grew up right here, fifty feet from this house, through the Depression. We were living here on Grand and Essex Street. There were stables on Henry Street, Madison, Cherry Street - horse and wagons. Cats you would see dying from the cold – it was unbelievable. No steam, no food, no heat, no lights: but people liked each other more. We were all poor. I’ve lived in an area of four or five square blocks most of my life.’

Ziprin’s apartment on East Broadway, off Grand Street, is packed with books on religion and spirituality and, for some reason, electrical engineering, along with an impressive collection of black fedoras he sports when his head is not under a yarmulke. In his mid-eighties, he suffers from chronic emphysema, requiring periodic trips to an oxygen tank in his bedroom. He can be pensive, silent and moody, or remarkably energetic and expansive, flailing his arms and raising his voice when agitated about the President of Iran (‘There’s no difference between his speeches and Hitler’s speeches! I listened to Hitler in German, he used to speak for hours, on amphetamines - the same psychosis, the same music . . .’) or the absolute necessity of filling Elisha’s cup to the brim on Pesach, when he found the stamina to preside over a four-hour seder, reading from a yellowed, dog-eared Haggadah that, curiously enough, barely mentions Moses. The food, donated by a local schule, is terrible; the wine, plentiful, and Lionel recounts the story of Exodus with the bravado and knowledge of the truly devout, his speech inflected with Yinglish, that peculiar Jewish-Yiddish-English dialect of the Lower East Side, in which the object of the verb somehow ends up in front of the subject. His hair and long flowing beard are white, his face is pale and wizened, but his eyes are dark, alive and sparkle with a mixture of mischief and wisdom.

As a child afflicted with epilepsy and rheumatic fever, Lionel Ziprin seemed to live in an alternative reality. From an early age, there were visions: ‘I thought I saw angels on the trees, passing East Broadway, way past the library. I saw them lying on the trees. I thought I was living in the Bible when I was a kid, in my grandfather’s house. I was in another world; the only thing that proved to me that I wasn’t living in the Bible was that I didn’t speak English till I was 10 years old.’

His childhood was troubled. At 5, he was kicked out of the yeshiva for laughing at the rabbis (‘I hated it! It was like a prison!’). Around the same time, his father left the household. ‘I looked for him for months by the window, he’d never come. He knew all the Jewish poets, the Jewish writers. He had to earn some money, so he became a lawyer, later he worked for Columbia University. He did the letter S for the Thorndike Semantic Dictionary. When I was 19 I worked in his office on Park Avenue. I was working for the Seven Arts and the Overseas News Agency and the Jewish Telegraphic Service, all at once. We had machines bringing in news of Auschwitz, the horrors of the war.’

Ziprin began writing poetry, and received a scholarship to Columbia University, impressing the critic and scholar Mark Van Doren with articles on Thomas Wolfe, Keats and the Greeks; however, his studies were cut short due to poverty, and his almost dogged inability to fit in. Nonetheless, he wrote several long poems, ‘What This Abacus Was’ and ‘Math Glass’, published after the war by his friend Asa Benveniste, the founder of Trigram Press. ‘He was a Turkish Jew; he had a very good poetry magazine, called The Trigram. I knew him in college; he went into the army. Later, he stayed in Paris. There were a lot of people who stayed in Paris; it’s a literary place and you can always go to Morocco. “Moroc” they call it, and you can get all the free hashish you want, and come back. He and a guy called Themistocles Hoetis, this guy George Salamos, published a magazine called Zero; George came to New York, and he said: Give us what you got. So I gave them “Math Glass”, and he published it and somehow T. S. Eliot got a part of it, and wrote me a nice little letter about it.’

Through the late forties and into the fifties, Ziprin also cranked out comic books for Dell Publishing. At the time, DC Comics had a lock on the superhero genre. ‘You couldn’t write about Superman or space. Dell made contracts with all the movie companies and I wrote a series of comic books on every battle in the Pacific and European theatres. They gave me the theme, or movies would come out, big movies; they handed me the script, and I had to put it into comic book form. All I got was ten dollars a page: six boxes, balloons and lines, and I had to sign away everything, that it was not my property, no credit. But I was America’s best-selling writer of comic books, my comic books sold in the millions of copies.’

In 1952, Ziprin married Joanna, an artist and animator, a great beauty later reputed to be the inspiration for Bob Dylan’s ‘Visions of Joanna’. Joanna was - in the conformist Eisenhower America of the 1950s - a beatnik, and she introduced Lionel, a devout Orthodox Jew, to be-bop jazz, downtown bohemia and the avant garde art scene.

On the day following his marriage to Joanna, Harry Smith, an extraordinary polymath and experimental filmmaker, appeared at Ziprin’s door. ‘I had my wedding in my grandfather’s synagogue. We had a seven-flight walk-up on 88th street near the river. A little rooftop. Pigeons. The next morning, the morning after the first night of the wedding, there’s a knock on the door. Who the hell is knocking, nobody knows where we are! I open the door; I thought it was the stupid landlady or something. I jumped ten feet back! There is Harry Smith! He looked older than when he died! He was carrying Indian feathers, because he lived on the reservation, and he’s carrying an Eskimo seal made out of marble and he says [gravels his voice in imitation] “Well, are you Lionel Ziprin?” So Harry comes in, and from then on, for the next ten or twelve years, he’s there every night for dinner.’

Smith’s parents were part of the early Modern Spiritualist movement in the United States. His mother taught on the Lummi Indian Reservation where Harry recorded many Lummi songs and rituals; he went on to develop an important collection of religious objects. An obsessive ethnomusicologist, he culled an Anthology of American Folk Music from a massive personal collection of 78 rpm records. Featuring then obscure artists like Blind Lemon Jefferson and the Carter Family, it was released by Folkways in 1952 and the bible of the Greenwich Village folk scene, credited with sparking the folk and blues revival of the late fifties and early sixties.

Smith could talk for hours on subjects as arcane as the tarot, the philosopher’s stone, Indian feathers, exotic plants, extinct religions, his collection of 30,000 Ukrainian Easter eggs, Aleister Crowley and various forms of lost or forgotten magic. Obsessive, abrasive, erratic, a bohemian’s bohemian, he frequently borrowed money, which just as often was never repaid.

‘He would go to the library all day long. He was such a fantastic artist; he could copy all the Latin manuscripts like forgeries, the Hebrew and everything, onto parchment. And at night he would bring me all these things. He had one gesture when leaving: he stooped down and kissed my feet. Man, I was ready to take his teeth out! He says, “My master!” My family adopted him. My father, my mother bought all his cameras, paid for all his film courses in New York. Mostly Jewish people supported Harry Smith.’

In 1952 Ziprin and Joanna invited Smith to the annual Lag Ba’Omer party thrown by Ziprin’s grandfather, the Reb Abulafia, in Manhattan’s Clinton Hall. It was held in honour of the second-century Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai (Rashbi) of Safed, the Israeli holy city where Lionel’s grandfather was also born. Rashbi is, of course, the author of the Zohar and the most renowned Kabbalist in history. Along with his son Elazar, he hid in a cave for thirteen years, after the Rabbi Akiva, his teacher, and 24,000 of Akiva’s students were tortured and killed by the Romans. ‘So every year, on Lag B’omer, the thirtieth day after the second day of Passover, hundreds of thousands of people, from all over the world - mainly Sephardic Jews from the Arab countries - travel there, to dance on the night of his departure. And it was in this cave, that my grandfather went to see, that all his revelations about Kabbala came to him. So since my grandfather was in America, on Lag B’omer night he would rent Clinton Hall, a few hundred people would gather, and my grandfather would sing all these Kabbalistic songs all night long. I remember it since I was a child. I thought that my grandfather was an incarnation of Shimon bar Yochai, but I never said that to him or to anybody.’

Abulafia’s singing, ‘a wonderful goulash of Ashkenazi, Sephardic and Arabic flavours’, according to Jewish folklorist Yale Strom, made an immediate impression on Smith. ‘Harry came and was astonished at the whole thing. He recorded all this, my grandfather singing. As we were leaving the party at 3 in the morning, my grandfather wondered: Who is this fellow? He looked very Jewish; he’s very hunchbacked, thick glasses, and dying of starvation, since he only eats yogurt because he thinks everyone’s poisoning him. Harry’s carrying the little tape recorder, so my grandfather asks him in Yiddish, “What is this?” Harry speaks no Yiddish, my grandfather speaks no English. So I said, “This is a tape recorder.” Harry gets the idea. My grandfather hears his voice on this little machine. He can’t believe this! Magic! So Harry says, maybe we can arrange for me to record him, and he spent lots of money on tape and on all these machines.’

Two years later, Abulafia gave Harry Smith $35,000 to set up a recording studio in his yeshiva, the Home of the Sages of Israel, where, in his characteristically obsessive style, he recorded the rabbi every day for almost two years. The sessions yielded 15 different vinyl LPs: eight of the rabbi telling stories in Yiddish, seven of him singing liturgical songs in Hebrew. ‘Authentic, you don’t hear that stuff.’ With Lionel’s encouragement, Smith showed Abulafia his films, abstract films, colour studies. My grandfather got up, and sighed, “From another world.” Another time he says: “Harry was Jewish in another lifetime.”’

A thousand copies of each LP were produced, 15,000 in total, of which approximately 300 survive. One of the albums was distributed by Folkways, a label that was later bought by the Smithsonian. Abulafia signed a contract, but, shocked by how little he would receive in royalties, ended the collaboration. Soon after he died, through a combination of family arguments and a lack of awareness of their value, most of the records were destroyed in a basement flood.

Around this time Ziprin and Joanna started a greeting card company, Ink Weed Arts, employing Smith, as well as future experimental filmmakers Bruce Connor and Jordan Belson. Lionel and Smith designed unique 3-D cards, based on hand-drawn images of the Tree of Life. In a 1973 interview with Paul Cummings for the Smithsonian Institution’s Archives of American Art, Connor is candid about the quixotic nature of the Ziprin’s commercial enterprise:

When I came here to New York I think in ‘51 or ‘52 I met Lionel and Joan Ziprin. I designed some greeting cards for them. At that time they were making what we call ‘studio’ cards. Harry Smith was designing three-dimensional Christmas cards. They were satirical, with a little bit of black humour, and totally unpopular. They were called Ink Weed Studios. They were totally disorganized as business people. They were not a business. They were very much involved in Kabbala and magic theory, and Tibetan mysticism as well. Harry Smith was very much involved in that. They would tell me stories, fantasies. Lionel gave me a book of Kabbala that was all in Hebrew. I could not read it, but he said it was good for me and it was good luck to have. And it has a mandala image in it.

This was also the period when Ziprin wrote Songs for Schizoid Siblings, a collection of zany children’s poems based on both Mother Goose rhymes and the teachings of the Kabbala.

In the late fifties, Ziprin’s lectures on the Zohar, organized and hosted by the beat photographer and poet Ira Cohen, fed the chronic beat thirst for mystical revelation.

No less surprising was Lionel’s unlikely association with some of the greatest jazz musicians of the century, particularly Thelonious Monk and Charlie Parker. ‘I had four children already, living in a basement on 7th Street and I had a kosher house, and Joanna has become the hostess with the mostest, she’s keeping a free kitchen. When she wakes up 3 o’clock in the morning she starts cooking and all the birds come. Thelonious Monk would come to my house between sets. He was at the Five Spot and I was living on 7th Street. Where does he go between sets? Comes to Lionel’s house, sits in the rocker! He’d come in the door - we lived in the basement, the Magic Basement. And he comes in the threshold of the door, the mezuzah on the door - he at least noticed it - and on the threshold, he’d do the hucklebuck. Then he’d come in, and sit on the rocker. The kids smelled his atmosphere, and they went: Oh, oh, Thelonious! And they’d climb on him. He was smiling, he never much talked, nothing to say. We went every night to Birdland; but not Friday night, not shabbos night. They knew I was Jewish, I had a beard, just a short beard. I told my Zaide, he’s like a great teacher, Charlie Parker.’

But the project which occupies Ziprin now is the Harry Smith recordings of the Reb Abulafia. Shortly before his grandfather’s death in 1955, Lionel promised his grandfather that the recordings would not be lost or forgotten and that his grandfather’s music would be made available to the world – a promise that, even at 82, Ziprin has every intention of keeping.

‘I need a little money to finish the liner notes, do the graphic designs. For the liner notes I need some scholarly people. I’m beginning to meet them. Just the other day, I had the world’s most highly paid cantor here.’

Indeed, the Rebbe Abulafia remains very much alive for his grandson, who regularly walks the short distance to Bialystocker Street, to the current incarnation of his grandfather’s schule, the House of Sages, a home and yeshiva for retired rabbis that Abulafia helped found in the early 1930s with Rabbi Shmuel Aaron Rubin, who became the famed ‘Radio Rabbi’ presiding over ‘the Court of the Air’ (a Jewish mediation board that broadcast its sessions over Yiddish radio stations from the mid-thirties to 1956).

‘It was on Henry Street, and Rubin insisted that they don’t sleep there, he didn’t want the expense of having to get OKs from the housing department and the buildings department. And my grandfather said No, this has to be a home for them, a home. They don’t fit anywhere, and their children are already American. You know, progress: cut the beard, become a lawyer, a doctor, go to college, get a good job, money. So where are they gonna to spend their old age? In a nursing home? They’ll die. Where are they going to go at night?

Finally he couldn’t get along with Rubin, and they broke up. He said: You keep this and I’ll go. So he went and he started the Home of the Sages of Israel on East Broadway, which is what he wanted.’

The Rebbe Abulafia died in 1955 when the city began knocking down the Home of the Sages of Israel to build the housing projects his grandson now lives in. ‘When he saw the steel ball on the chain, he lost his mind, it killed him; he died before his time. Then there was no money left to build the synagogue, crooks came and stole the two million dollars of city compensation for the home. So my grandfather wasn’t here and the city didn’t want to start lawsuits against rabbis. Finally the Satmar came. They’re smart. They bought the site and they have it to this day; they made a gold mine out of it. It’s a modern building and the top floor is a secular nursing home, it’s Jewish and it’s other religions, otherwise the government won’t give you money. It’s very spic and span – it’s too clean for a synagogue! And downstairs - the learning goes on.’

There are still visions. He still sees angels. ‘I see them still occasionally, not so much anymore. It’s no big thing; it’s only another species. God created all these things; fish, insects, monkeys, parrots, birds. Angels are one more species, there are different kinds of angels just like there are different kind of people, different kinds of fish, different kinds of animals, there’s a species called angels.’

Lionel believes he had a brief encounter with the Angel of Death while waiting around for some test results recently at Bellevue Hospital. ‘He was in dirty clothes, he looked around the age of 70 or 80; I couldn’t tell whether He was Hispanic, Black or Chinese. He was walking – I always look when I see an angel at the shoes, to see if there is any space, even a quarter of an inch between the bottom of the shoe and the floor, you know? And I see him coming towards me, and I’m waiting for a guy to come, if he can ever find the cab to go home at 5 o’clock, and the Angel of Death is coming closer and I say: Well, I have to sign these papers, I got them in my hand, right? It’s coming towards me, the picture’s getting more complete, it’s not the first time I’ve seen an angel, right? I don’t want to look at it; I turn my face the other way, you know, to the door, looking out so I don’t have to see it. It’s going to pass; I don’t know what it’s going to say. So it passes about six inches from me, it doesn’t stop and as it passes it says . . . “Zay gezunt” [Yiddish for “Stay well” or “Goodbye”]. I had no idea! “Zay gezunt”? It says “Zay gezunt”.

Its face is like, maybe it’s smoke, it’s not clear, I don’t know if other people see this, it is not an apparition. Why should it be an apparition?’ Lionel asks, a smile on his face, an impish twinkle in his eyes. ‘If it’s an angel, it’s an angel! It’s a real thing - isn’t that wonderful?’

David Katz has written for a variety of publications, including High Times, East Side Review, Rap Express and Girls Over 40. He lives in Manhattan.

© 2006 Jewish Quarterly | All rights reserved

The House of the Sages Memorial

We regretfully wish to inform of the passing of

Rabbi Ziprin passed away this Sunday Morning, he will be interred in the Holy Land.

Rabbi Ziprin was a cherished member and senior Rabbi at the Society of the House of the Sages, for over 30 years.

The Aron will stop at the Anshe Mamod at 3:00pm

For all who wish to pay their final respects.

Woefully! What tribute can we goodbye to somebody who gave so much of himself so eloquently for Kehila, Alas! We will honor his memory by devoting our lives to the Eternal values of our heritage he transmitted to us from the holy sources of his family and the example of his life. There can be no other fitting tribute to Rabbi Ziprin a link from days gone by, a witness to the hallowed past that words cannot describe, it was truly a priviledge to know him. His legacy survives with his children they will always cherish their father's memory in their hearts.